Hi, I'm Thomas Frank, this is Crash Course Study Skills.

Benjamin Franklin once took a few seconds out of his busy schedule of being a god of lightning to remark,

"By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail."

This is doubly true when it comes to preparing for your exams.

So today we're going to guide you through the process of creating a study schedule, reviewing effectively so that you master the material,

and doing it all without cracking under the pressure, quitting school,

and building a career as an internet personality who tells people how to do well in school despite never being able to complete it yourself.

[Theme Music]

As we've discussed already in this series, learning takes time.

Encoding new information into solid memories is a physical process that doesn't happen overnight,

and it requires multiple exposures or recollections which need to be spaced out.

But, as we've also discussed, your brain isn't built to make long-term focused decisions.

It's hard-wired to care a lot more about now than later, which is why some of you are heavily considering booting up Overwatch after this video ends

instead of finishing that math assignment that's due tomorrow.

What this all means is that the structure of the stuff sitting up in your cranium isn't up to the task of preparing for a test –

so you need to build external structures to help it out.

And, arguably, the most important one is a study schedule.

I recommend building your study schedule directly into the calendar you're already using for everything else,

as it's crucial to figure out how you're going to balance your time between studying and finishing all the assignments and homework that lead up to the test.

The first step to doing this is to figure out the exact dates and times of your exams, and then to add them to your calendar.

In my Google Calendar, I actually have a specific calendar that's colored differently from all other events, and that lets me see those dates and times at a glance.

I'd also make sure to include the location for any exam that's being held somewhere other than that class's normal room – which happened pretty often for me in college.

Once those dates are safely stored in your calendar, work backwards and schedule study sessions during the 3 or 4 weeks leading up to your exams if they're finals.

If it's a smaller exam, two weeks will probably do.

If you've got a lot of homework or group projects, try to schedule time to work on those as well.

When it comes time to actually sit down and study, try to replicate the test conditions as much as you possibly can.

Memory is very context-based, so if you can review the material under conditions that are similar to those of the test, recalling it will be much easier when you're actually taking it.

So, how do you do this?

Well, first try to get as much information about the test as possible.

Ask your teacher – or look at the syllabus – to find out what material will be covered,

whether or not the test will be comprehensive, how many questions there will be, and how long you'll have to answer them.

You'll also want to know what types of questions you'll be up against – will they be multiple choice, true/false, short answer, or essay?

Lastly, don't forget to ask about what materials will be allowed, such as scratch paper or calculators.

Once you have all those details locked down, the next step is to try to get your hands on practice tests, or tests from previous semesters.

You can ask your teacher if they have any that they're willing to give out as review material,

and if you're in college, theremight be a fraternity, or sorority, or some other student organization that keeps a test bank you can dig through.

There's also an online test bank at Koofers.com that contains old tests from lots of universities, so that's worth a look as well.

Now that you've gathered all of your resources, it's time to study.

But where should you do it?

While most of your studying will probably happen in your established study space,

you should also try to do at least one or two sessions in the actual classroom you'll be tested in – or at least some other classroom with a similar look and feel.

As I mentioned earlier, memory is context-dependent.

Our brains are better able to recall things they've learned when we're in a similar context to the one in which we originally learned or reviewed the material.

In fact, one study published in 1975 demonstrated how subjects who learned lists of vocabulary words underwater in scuba diving gear

were much more easily able to recall those words when they went back underwater again, as opposed to when they were on dry land.

Don't stop at the location, though.

Also spend some time studying under the same constraints that you'll have during the test.

Set a timer to simulate the test's time limit, and quiz yourself without having access to your textbook, notes, or any other materials that you won't have during the test.

And notice that I said "quiz yourself" here.

The best way to study for a test is to do it actively and to focus on recall –

to force yourself to actually pull facts and answers up from the depths of your memory banks.

Now, at this point you might be thinking to yourself,

"Tom, this all sounds good, and the fact that you're wearing one of Hank Green's shirts makes you a lot more trustworthy

BUT how am I supposed to quiz myself in the first place – especially if my teacher didn't give me any practice tests?"

Well, you make your own quizzes, of course.

Now, if your teacher gave you a study guide, then that's going to be your #1 resource for creating these quizzes.

Just take every concept listed on the guide and convert it into a question.

If you don't happen to have one of those, then do the same thing with your lecture notes.

Look through them and create questions out of headings, main concepts, and even case studies.

Now, when you're forming your questions, in general you're going to want to emulate the test as much as possible.

However, there are a few types of questions that lend themselves perfectly to certain formats.

For example, facts and vocabulary terms are great candidates for flash cards.

Studying flash cards is another form of quizzing yourself, and they have one great benefit – you can study them from both sides.

If you're studying for a chemistry exam, one card can ask you what the chemical symbol for Neon is, and if you flip it over, it can also make sure you know what Ne represents.

This ensures that your brain can make the connection no matter where it starts.

And when it comes to subjects like math or physics, where your questions will usually take the form of equations or problems,

you want to spend the majority of your study time actually working through those problems.

Spend a little bit of time familiarizing yourself with formulas and concepts, sure,

but spend way more time practicing and making sure you can actually perform the operations yourself.

Now, as you spend time actively solving these problems, you're inevitably gonna run into things you don't know how to solve.

When you do, it's important to know when to ask your teacher for help – and how to do it correctly.

Let's go to the Thought Bubble.

Dale Corson, the 8th dean of Cornell University and a professor of chemistry, offered some advice to his students for how to effectively ask for help.

Before going up to the professor, he said, ask yourself: What is it – exactly – that I don't understand?

This obvious-sounding piece of advice is worth stating plainly because, as Corson puts it,

many students would come up and say – with a general sweep of the hand – "I don't get this."

The moment they encountered a tough spot, they'd disengage and let their brain essentially give up.

Don't do this.

When you become confused, spend 15 more minutes trying to solve the problem on your own.

Work line by line through the problem until you know precisely where the confusion begins.

Also, try to write down the solutions you've tried so far.

Doing this essentially documents the problem and creates context for the person who will eventually help you –

and it might actually help you solve the problem on your own as well.

In the world of software development, programmers who are stuck on broken pieces of code will often use a technique called Rubber Duck Debugging,

which involves explaining the code and thought process behind it to a rubber duck.

The idea here is that explaining the problem to a non-expert – in this case, a cute little duck on your desk –

forces you to think about it from a different perspective, which will often reveal the solution.

Additionally, going through this process will show your teacher that you've truly put in some effort and aren't just coming to them for help out of laziness.

And that's a great way to earn their respect.

Thanks, Thought Bubble.

Now, if you want another really effective way to solidify the material quickly, do a cheat card exercise.

Remember that really cool teacher that once let you write whatever you wanted on an index card and bring it with you into a test?

Because I do, and in my book, that teacher was almost as cool as the one who let us play with magnesium and bunsen burners unsupervised – for science, of course.

Now, most teachers aren't going to let you bring a cheat card into the exam – but that shouldn't stop you from making one.

The thing about an index card is that it's small.

And even though I pushed the limits of how tiny a human hand can write whenever I got the opportunity to make a cheat card, there's only so much I could fit on it.

And due to that limitation, I had to be very choosy about what I put on the card –

which resulted in a tiny piece of cardstock containing the most important information on the exam.

And since I'd just spent an hour looking all that stuff up and writing it down in teeny tiny letters, I was interacting with it – actively – the whole time.

That's the beauty of a cheat card exercise.

Even if you can't bring your card with you into the test, you spend a concentrated block of time selecting and writing down the most crucial information.

It's a great preparation technique.

Speaking of great preparation techniques, the last one we're going to cover today is not studying.

At least some of the time.

Students often believe that they should be spending all of their time studying if they want to do well, but remember:

how well you do is determined by the both the time you put in and the intensity of your focus.

And to enable your brain to focus intensely, you have to give it some time off.

The cycle of work and rest has to be respected.

So when you're crafting your study schedule, give yourself time for breaks.

That includes short breaks during review sessions,

as well as some longer periods where you can de-stress and reward yourself with some of that good old high-density fun.

Doing this will ensure that you're alert, attentive, and happy – well, as happy as somebody with a calculus final coming up can be.

And if you're creating your study schedule well in advance, you should have no problem giving yourself time for these breaks while also leaving enough hours open for studying.

Speaking of breaks, it's time for one now!

Hopefully this video has given you enough direction to successfully prepare for any exams you've got coming up.

Next week we'll be tackling test anxiety, but I can give you a bit of a spoiler up front:

Good preparation – especially the type that replicates the test conditions – is one of the best ways to calm those nerves.

So get to work making that upcoming test feel like a familiar old friend, and I'll see you next week.

Crash Course Study Skills is filmed in the Dr. Cheryl C. Kinney Crash Course Studio in Missoula, MT, and it's made with the help of all of these nice people.

If you'd like help to keep Crash Course free for everyone, forever, you can support the series over at Patreon, a crowdfunding platform that allows you to support the content you love.

Thank you so much for your support.

For more infomation >> Minecraft: Story Mode - Season 2 - Episode 3 [Full gameplay] - Duration: 1:37:24.

For more infomation >> Minecraft: Story Mode - Season 2 - Episode 3 [Full gameplay] - Duration: 1:37:24.  For more infomation >> Bracing For Impact - Duration: 2:23.

For more infomation >> Bracing For Impact - Duration: 2:23.  For more infomation >> My Oh My - Leonard Cohen (subtítulos en español) - Duration: 3:38.

For more infomation >> My Oh My - Leonard Cohen (subtítulos en español) - Duration: 3:38.  For more infomation >> Live Doppler 13 weather forecast - Duration: 2:50.

For more infomation >> Live Doppler 13 weather forecast - Duration: 2:50.  For more infomation >> Major downtown highway project planned - Duration: 2:14.

For more infomation >> Major downtown highway project planned - Duration: 2:14.  For more infomation >> Europas Zukunft - Duration: 1:11.

For more infomation >> Europas Zukunft - Duration: 1:11.

For more infomation >> Citroën C3 PURETECH 110 S&S SHINE NAVI/BT/17'' - Duration: 0:56.

For more infomation >> Citroën C3 PURETECH 110 S&S SHINE NAVI/BT/17'' - Duration: 0:56.  For more infomation >> Continue Jejuando Zona de Guerra Espiritual - Duration: 16:42.

For more infomation >> Continue Jejuando Zona de Guerra Espiritual - Duration: 16:42.

For more infomation >> 19/09/2017 21:40 (M3, Chertsey KT16, UK) - Duration: 2:59.

For more infomation >> 19/09/2017 21:40 (M3, Chertsey KT16, UK) - Duration: 2:59.  For more infomation >> Xóa Sổ Mụn Đầu Đen Sau 1 Đêm Mà Không Cần Nặn Chỉ Bằng Chanh Và Muối - Duration: 5:14.

For more infomation >> Xóa Sổ Mụn Đầu Đen Sau 1 Đêm Mà Không Cần Nặn Chỉ Bằng Chanh Và Muối - Duration: 5:14.

For more infomation >> '란제리 소녀시대' 채서진, 인교진 속옷 벌칙에 항의 "폭력이다" || SML TV - Duration: 3:07.

For more infomation >> '란제리 소녀시대' 채서진, 인교진 속옷 벌칙에 항의 "폭력이다" || SML TV - Duration: 3:07.  For more infomation >> '왕사' 윤아, 독차 마시고 각혈·실신..생사 위기 || SML TV - Duration: 1:55.

For more infomation >> '왕사' 윤아, 독차 마시고 각혈·실신..생사 위기 || SML TV - Duration: 1:55.  For more infomation >> How I see Ela - Duration: 0:06.

For more infomation >> How I see Ela - Duration: 0:06.

For more infomation >> Kali Uchis - Nuestro Planeta

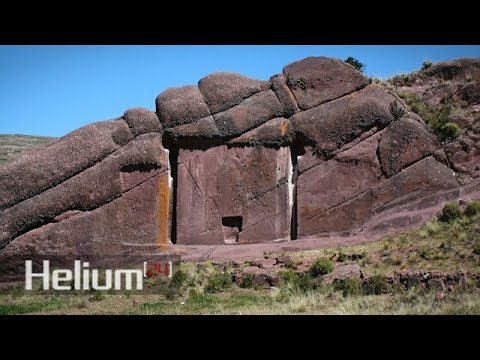

For more infomation >> Kali Uchis - Nuestro Planeta For more infomation >> La puerta de Hayu marca: Un ancestral portal estelar de los dioses en Perú - Duration: 5:31.

For more infomation >> La puerta de Hayu marca: Un ancestral portal estelar de los dioses en Perú - Duration: 5:31.

For more infomation >> Email Marketing Automation How Often Should You Email Leads - Duration: 2:13.

For more infomation >> Email Marketing Automation How Often Should You Email Leads - Duration: 2:13.  For more infomation >> Conchita und Russkaja mit "Wanted more" - Willkommen Österreich - Duration: 2:50.

For more infomation >> Conchita und Russkaja mit "Wanted more" - Willkommen Österreich - Duration: 2:50.  For more infomation >> Very Emotional Dua By Maulana Tariq Jameel Sahab - Duration: 11:56.

For more infomation >> Very Emotional Dua By Maulana Tariq Jameel Sahab - Duration: 11:56.  For more infomation >> OFF TO SEA | Meme - Duration: 1:16.

For more infomation >> OFF TO SEA | Meme - Duration: 1:16.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét